BSNC shareholder and elder John Tetpon is a Pulitzer Prize-winning writer. John has graciously agreed to share with us a series of stories he compiled from decades of travels across Alaska and the Lower 48. Here is the story of four Hoonah orphans in his own words:

My late friend Frank Mercer, a longtime Anchorage resident from Hoonah, was a well-known Tlingit who knew everybody. When I saw him sitting on a bench at Sears Mall one day, I joined him. He was eating an ice cream cone and I got one for myself.

We sat there and talked about fishing and the weather, and then he said, “I’m going down to Homer tomorrow to see your mom and dad.” He added that he often went to Homer and parked his camper in Dad’s yard.

“I didn’t know you knew my parents,” I said.

“Yeah,” he said, “I’ve known them for years.”

Then he told me an incredible story I never knew about. He said of how he came to know my parents. He said the captain of the Bureau of Indian Affairs supply ship North Star had dropped off four little Inupiaq children on the Hoonah beach on its voyage back to Seattle sometime in the 1920s.

“They were all alone, you know, just standing on the beach, four little ones about 4, 5, 6 years old. We saw them from our house and went down and took them home with us.” He added how his father and mother raised them from then on as their own.

The four were my Dad’s siblings, Ann, George, Edward, and Axel Jackson. The captain said he put them on his ship in Nome to see if he could find them a home and family on his way south to Seattle. The captain said he stopped at every village and town along the way. No one volunteered.

Alaska was in the midst of the Spanish Flu epidemic at the time and people were dying by the thousands. A report from that time told of people dying in every village, with at least 10 a day in the Nome area gold fields where my father’s dad, Eric Jackson, worked as a mining engineer. Jackson, who was from Finland, trekked across the Chilkoot Pass on his way north to the Nome gold mines.

The Spanish Flu took many lives, with some villages entirely wiped out. Both of Dad’s parents died of the Spanish Flu leaving five children. Dad was a two-year-old at the time. The Tetpon family later adopted him. The captain said he didn’t want them to leave the territory. Hoonah is located in Southeast Alaska and was the last stop on the North Star’s voyage back to the Pacific Northwest.

The four grew up in Hoonah as family members of the Mercers and later, Ann, George, Edward and Axel were sent to Chemawa Indian School in Salem, Oregon. Aunt Ann was a beautiful lady who hob-knobbed with the Hollywood crowd in her heyday.

My uncle George played clarinet in his younger years and was a member of several orchestras in California in the big band era. He married and settled in Fresno where his children and grandchildren remain. I have never met him or any members of his family.

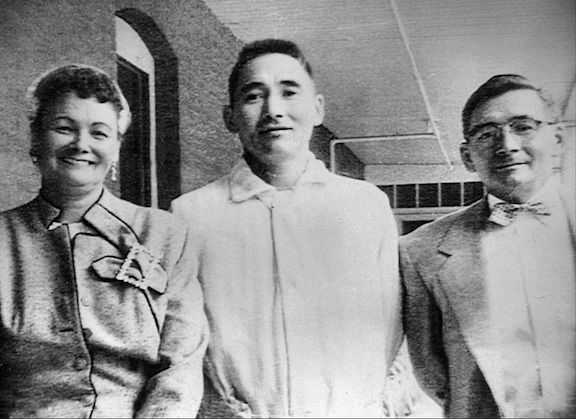

Ann and Dad met for the first time back in the 1960s after more than 40 years apart. That made headlines in the Anchorage Times.

Chemawa Indian School dates back to the 1870’s when the U.S. Government authorized a school for Indian children in the Northwest. The official philosophy at that time was to integrate the Indian population into general society through education. That was the intent.

In all the 20-some years I knew Frank Mercer he never mentioned his friendship with Dad. I guess it was the right time and place when he shared his story that day at the Sears Mall.

Funny thing is Frank always treated me like family.

Frank is gone now, but I’ll bet he’s happy wherever he is. He was just that way. If it had not been for the Mercers, we might not have known about our relatives.